The pathophysiology of anxiety is the way that the pathology of anxiety manifests itself in the body. It may be easier to think of it as the path anxiety follows through your body to result in the anxious state. While scientists think they know how anxiety is produced, the body is a complex system and in many ways, science is still learning how it really works.

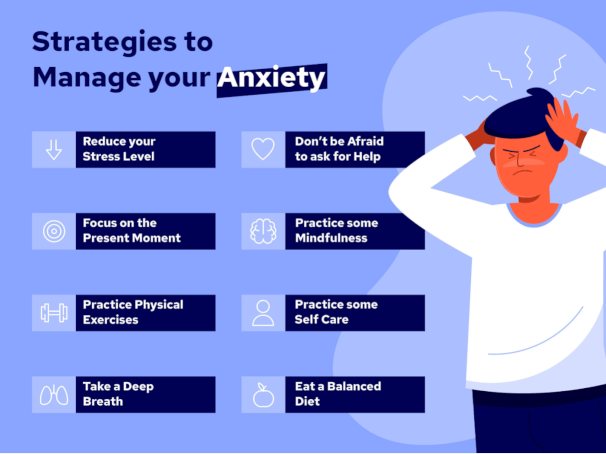

This article will describe how anxiety is thought to manifest in the body, and what you can do to overcome it.

Causes of Anxiety

Anxiety is an incredibly complex condition. Some people believe it's biological. Others believe it's learned. Most likely it is somewhere in between. But one thing no research denies is that no matter the cause, anxiety can be stopped.

The Amygdala: Where It All Starts

The amygdala, a pair of small, almond-shaped clusters of neurons near the base of the brain, is thought to be the starting point of anxiety reactions. While it is not responsible for what you think when you encounter anxiety-producing stimuli, it is responsible for what your body does.

The job of the amygdala is to manage the storage of memories according to the strength of the emotional reaction associated with the memory.

The right amygdala, primarily responsible for the action, is generally more active in men than in women. The left amygdala, on the other hand, is primarily responsible for storage of the details traumatic memories and prompts more thought than action. This amygdala is more active than the right in women, and in persons of both genders who have anxiety disorders.

The amygdala, once triggered, sends distress signals to the other key parts of your brain. The most important parts are discussed below.

The Medulla Oblongata: Where's My Air?

The amygdala starts by communicating with the parabrachial nucleus, a structure looking something like a small gray horseshoe, which, in turn, triggers the medulla oblongata.

The medulla oblongata, located on the lower part of the brainstem near the other more primitive brain structures responsible for fight or flight, is the part in charge of the involuntary functions of your body, including your heart rate, and the rate of your breathing, and vomiting.

Once tagged by the parabrachial nucleus, the medulla oblongata starts sending word to the lungs and cardiac muscles that extra air is needed for circulation to the muscles of the body by way of the blood.

When the body doesn't actually need to fight or flee, the quick breathing and extra air that the medulla oblongata has sent for overwhelms the body and results in both dyspnea, or shortness of breath, and hyperventilation.

The Nucleus Ambiguus and Hypothalamus: Getting On Your Nerves

The nucleus ambiguus, located just below the medulla oblongata, is the part that receives its urgent call for more blood to transport extra oxygen. In response, the nucleus ambiguus causes the body's arterioles to constrict by way of its interaction with the parasympathetic nervous system, which makes the heart pump harder and faster.

Similarly, the hypothalamus, when triggered by the amygdala, sets off all kinds of activity in the body's other nervous system: the sympathetic nervous system. The sympathetic nervous system is in control of the majority of the body's fight or flight response.

The fight or flight response essentially prepares your body for anything. Your heart, your lungs, and your muscles are all required to equip the body with everything it needs to move fast and effectively. On the plus side, you really are ready to fight or to fly when you are experiencing this response, even if it's only anxiety and there's actually nothing to worry about. On the downside, experiencing fight or flight all the time for no good reason can be exhausting. This has much to do with the sympathetic nervous system's triggering of the adrenal gland.

Adrenal Medulla: Energy Plus Crash

Your sympathetic nerves alert the adrenal medulla to release that famous hormone that goes by the name of adrenaline into the body, along with a small amount of dopamine, making the body initially feel better than it otherwise would (which is known in combination as the adrenaline rush). The adrenaline tells the brain to release a type of neurotransmitter called epinephrine, which boosts both blood pressure and blood sugar, making the blood sugar (along with the body's stored fatty acids) available to be turned into quick energy by the muscles.

This rush has literally been known to give people seemingly superhuman powers, including extreme strength and speed. However, it comes at a price. Post-adrenaline rush, the body crashes, taking the dopamine or reward chemical with it and making the body feel tired and unhappy. Your muscles, particularly those in your chest, may also be tired and even sore from the tension that helped to bring them their extra fuel, and from the rapid breathing that the lungs were doing to keep the blood of the heart supplied with oxygen.

The amygdala is connected to the prefrontal cortex of the brain by way of neuronal pathways, which is the part of your brain that thinks about your experiences rather than simply reacting to them. The amygdala, while technically connected to this part of the brain, does not itself think. This means that although your amygdala reacts just like anyone else's, the thoughts and memories stored by the amygdala in the cortex are your own, and therefore what the amygdala reacts to can vary widely.

The hyperactivity of the amygdala can only tell you that you may have an anxiety disorder, but not what specific type of disorder you have. However, what your amygdala is triggered by is a key factor in defining what anxiety disorder you have. It may be virtually anything, from reminders of past events to crowded spaces, to disorganization, to spiders, to triggers inside you that may not even be known.

The frequency with which and duration for which you are troubled by the hyperactivity of your amygdala can also help to define your disorder, but it is the content of your prefrontal cortex, which you can explore by way of therapeutic sessions, journaling, or simply talking to a trusted friend or relative that is responsible for the disorder itself. You can conquer your anxiety and remind your body whose side it's on by using your brain to find out what memory or belief in your brain's prefrontal cortex is triggering your body's pathophysiological response.